Designing Spaceships So People Don't Go Crazy

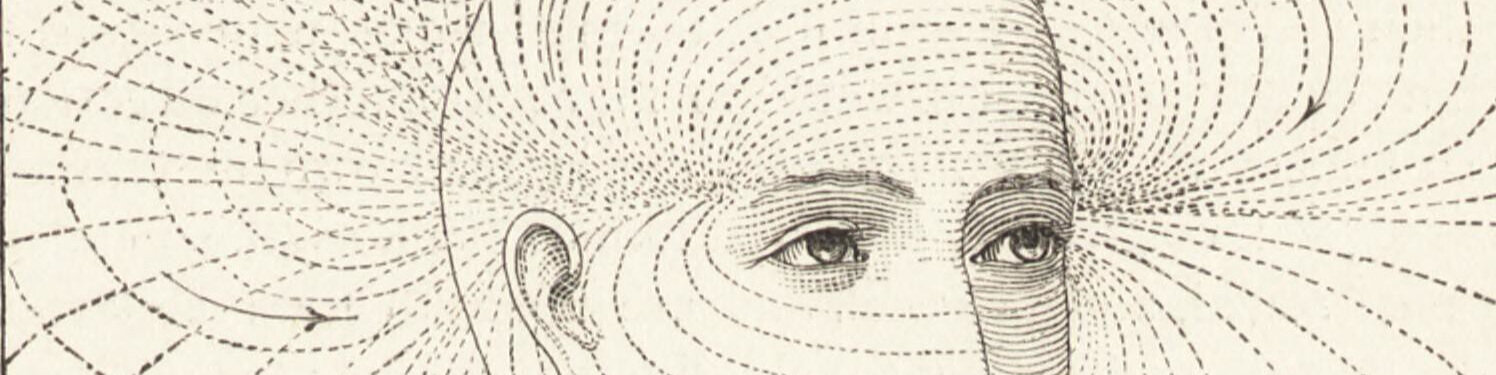

Spaceman, Digital collage of origiinal artwork and NASA spaceship schematics. Anne Kearney.

I have been interested in observing people and making art as far back as I can remember. My first memory of these interests colliding was in my 8th grade science fair project. I had just abandoned my attempt to create a plaster and wire frame model of an animal cell – not only was it not holding its form, but it was undeniably more art than science project – and I was relaxing with my mom’s copy of Betty Edward’s book, “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain.” As I poured over Betty’s examples, I found myself wondering whether people really do make copies of upside-down pictures more accurately than right side up ones. A science fair project was born.

My interest in the brain stayed with me and I went on to study cognitive science and environmental psychology. (What’s environmental psychology? See below to learn more.) I worked for many years as a researcher at universities, non-profits, and even for NASA, where, as my daughter once explained to a friend, I “helped design spaceships so that people don’t go crazy.” Although art was often in the backseat during those years, it was always along for the ride. I took classes and created whenever I could and explored a range of media before landing, for the past 10 years, on painting.

When I embarked on my adventure as a full-time artist, I thought I was leaving the world of psychology research behind. Instead, I have found that it has come along for this ride, continuing to impact the way I see the world and the art that I create. Every day, I see connections between psychology and art as I create, struggle, and observe, and it has occurred to me that others might also be interested in these connections.

What does psychology have to do with art? For one thing, research in psychology has much to tell us about how viewers interact with visual art – why our gaze is drawn to edges and contrast, why some colors recede and others advance. But psychology also has many insights to be mined related to the process of creating art and the wellbeing of artists: How is what we see biased by what we know and what does this mean for drawing and other visual arts? How do our environments support or squash our creativity? Why does everyone love a mystery and what does this mean for artists and their art? How can we tweak our environment to help ward off the mental fatigue of long days in the studio?

These are some of the topics that have been banging around inside my brain trying to get out. I plan to draw both on my background in psychology and my experiences as an artist as I write about relevant research, interesting tidbits, and insights that can support us in creating art and thriving as artists.

If you want to learn more, you can subscribe to my newsletter. And if there are any topics related to art and psychology that you would like me to write about, please let me know.

Crop of image from: The Principles of Light and Color, Edwin Babbitt, 1878. Public Domain.

What is Environmental Psychology?

When my husband and I first started dating, he finished describing me to a friend with, “… and she’s from Moscow, Idaho and she’s an environmental psychologist.” To which his friend responded, “Now I know you’re making her up because I’ve never heard of either of those things!” Moscow, Idaho, you can find on a map, but what is environmental psychology? How does nature affect our mental well-being? How can you design a neighborhood to encourage community? How do we help people find their way around a place? How can you present information so that it holds people’s attention? These are the types of questions that environmental psychologists seek to answer.

Environmental psychology is a part of psychology that takes the view that our surroundings are as important in understanding our perception, behavior, cognition and well-being as our brains. It recognizes that in addition to all the other things that make us “us,” we are, in no small part, products of our environment – both our evolutionary environment and our here and now environment. The interests for researchers in this field lie in the back and forth between people and their environment – between the brain and its surroundings. Environmental psychologists seek to discover how we can help support our environment and how our environment, in the broadest sense of the word, can help support us.