Advice from Space on Living in Covid-19 Induced Quarantine

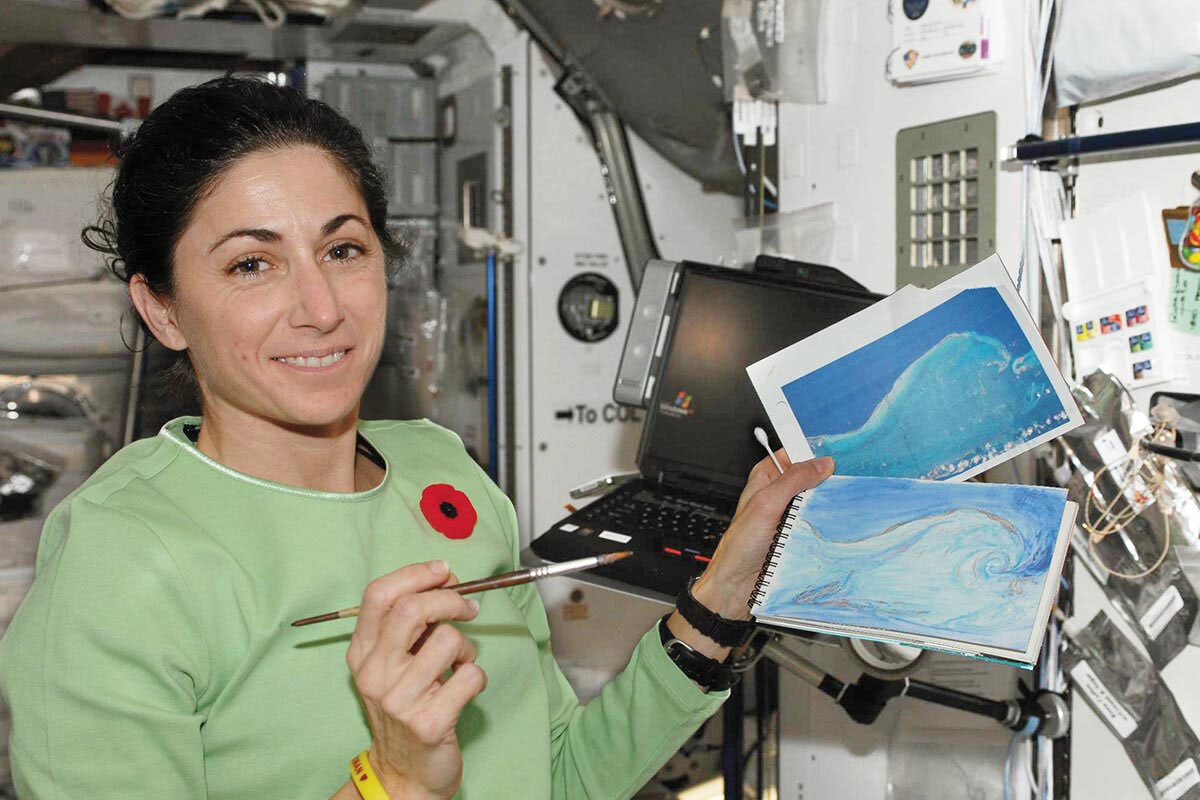

Astronaut Nicole Stott took her watercolors with her into space as a way to relax in her spare time. She is shown here onboard the ISS, with her painting and her reference photo of a view from space. Photo credit: NASA.

Earthbound people have benefited in many ways from space research. Smartphone cameras, scratch-resistant lenses, and infrared ear thermometers all got their start as inventions for use in space. And now, as many of us around the world shelter in place to flatten the Covid-19 curve, we can add one more thing to the list – strategies for maintaining our mental health in isolated and confined environments.

Several years ago, I was asked by NASA to research possible ways for astronauts to maintain their mental health during long duration spaceflight. This might seem relatively far down on NASA’s priority list, but as the science and engineering behind space exploration have developed rapidly over the years, the limits of living and working in space are now probably more psychological than technological. If people break down, the mission fails.

You think your house or studio is cluttered? This is a view into the Destiny lab on the ISS - on a tidy day. Photo credit: NASA.

For astronauts, rising to the challenge of an extreme environment can have positive psychological effects and evoke extraordinary levels of morale and cooperation. I see the same thing happening as people here on Earth rise to the challenges of the coronavirus. In the short term, people are remarkably adaptive and often cope surprising well in stressful situations. But over time, there can be negative consequences of living in a confined and isolated environment under extreme conditions – like increased stress levels, mental fatigue, irritability, and interpersonal conflict.

Fortunately, there are strategies for heading off these problems in space – many of which are relevant to those of us who are earthbound. Here are my top five suggestions, based on what I’ve learned from my research:

Astronaut Piers J. Sellers takes a meditation position as he floats on the mid-deck of the Space Shuttle Discovery while docked with the ISS. Photo credit: NASA.

1. Experiment with strategies to reduce your stress

Astronauts cope with stress in the same ways many of us do, although one of their favorite activities – relaxing while taking in the view of earth – is admittedly out of our reach. Different things work for different people, but common stress reduction techniques include meditation, yoga, exercise, gardening, and breathing exercises. The key with these techniques is to use them consistently.

There are also some changes you can make to your home environment to help lower your stress. On the International Space Station (ISS), reducing visual clutter and background noise can help reduce astronauts’ stress. (You think your house is cluttered? Take a look at the interior of the ISS!). Think about tidying the house and organizing your pantry (knowing what you have may have the added benefit of helping to stem the perceived need to hoard food and supplies). I went on a mad organizing and cleaning spree of my art studio and am still feeling the calming effects one week later.

If you live in an apartment like I do, noise might be more of a problem than usual with everyone staying home all day. The apartment above us has several young children and they are definitely a bit noisy (is that jump roping, I hear?). While things like noise cancellation headphones can help, so can trying to frame the noise in a positive light. When I hear what sounds like tap dancing or ping pong balls bouncing on the floor, I try to think, “Good thing those kids are being active – that’s probably really helping them.” And when I hear loud indecipherable talking, I try to imagine it as my own Spanish soap opera – what drama and intrigue are befalling the neighbors today?

What else can you do? Make a list of things that are stressing you out the most. What are some immediate things you can do to help ease that stress? For me, it was making sure our medical prescriptions were filled, organizing the refrigerator, and instituting a nightly tidying-up to keep the clutter at bay.

2. Use your brain

Having meaningful work is hugely important for helping astronauts adjust to life in space. Prolonged boredom and feeling useless can be stressful, whether you are in a space station or at home. As a start, get dressed in the morning and have a plan for the day – your activities don’t have to be earthshaking, but you should be doing at least some things during the day that engage your brain.

Artists, writers, and others who are used to working by themselves may be at an advantage here, as are students who are able to continue classes online and people who are able to work effectively from home. I am lucky that both my daughter’s university and my son’s school are continuing classes online and that my husband and I are able to work from home. Even so, we will all have more “free time” than normal. Maybe it’s time to try out some new recipes, get to those books you’ve been meaning to read, keep a journal or blog about your experiences, do a daily crossword puzzle, or finally organize the spice drawer.

We can all think about how we might help others, within social distance guidelines. What can we do for elderly neighbors, those with mobility issues, or those who are losing the means to support themselves? The inclination to step up and help others in a crisis is one of the beautiful things about being human and it is a win-win – people get needed help and the helpers find purpose and satisfaction. The world is in this together, and we will all have ample opportunities to help others.

Plants have proven to be good for mental health – even in space. Here, astronaut Peggy A. Whitson holds an experimental soybean plant. Photo credit: NASA.

3. Charge your mental batteries

Organizing family and work and staying on top of the news all while dealing with uncertainty takes a toll and can leave us feeling mentally wiped out. When our mental resources are depleted, everything gets harder – we have trouble focusing, snap at each other, and can end up feeling pretty helpless. Paradoxically, even some of the good things that keep us and our brain occupied – getting more time in your art studio, keeping up with work and school – can actually also deplete our limited mental resources and contribute to this fatigue.

How can we stave off this kind of mental fatigue? In space, sleep and exercise are front-line strategies for maintaining physical and mental health and they are non-negotiable. They are equally important here on Earth. For many people, getting outside to exercise is still an option; for others (like those of us in Spain) exercise is not, at the moment, a legitimate reason to leave home. But if you think that you don’t have room to exercise in your house or apartment, take a look at the tiny space in which astronauts effectively exercise on the ISS; your living room will suddenly look palatial.

European Space Agency astronaut, Thomas Pesquet, exercises on the Cycle Ergometer. Photo credit: NASA.

When we get more mentally fatigued than usual, strategies such as sleep and exercise may not be enough. We need something stronger – what environmental psychologists call a restorative experience – to encourage our brains to gently rest and reset. Luckily, one of the most effective things may be just outside the window. Nature, in its many forms, has been shown to be powerfully restorative – reducing mental fatigue and stress, and improving mood and behavior. Some of you are still able to get out and walk and you should take advantage of that, picking a route with the most nature. For others, even small doses of nature have been shown to be beneficial — sitting on the terrace, spending quality time with your houseplants, or even simply looking at a view of nature in the urban landscape from your window.

Do monitor your screen time. Social media is full of suggestions for binge worthy shows and there is a place for that. Screen-related activities can help pass the time and take our mind off things; but studies have shown that although people might think videos, video games, and the like are relaxing, when it comes to our brain’s mental resources too much screen time can leave us mentally fatigued, sluggish, and irritable. Likewise, while we should all stay informed, binging on news may actually lead to more stress. Be mindful of what works – and doesn’t work – for you.

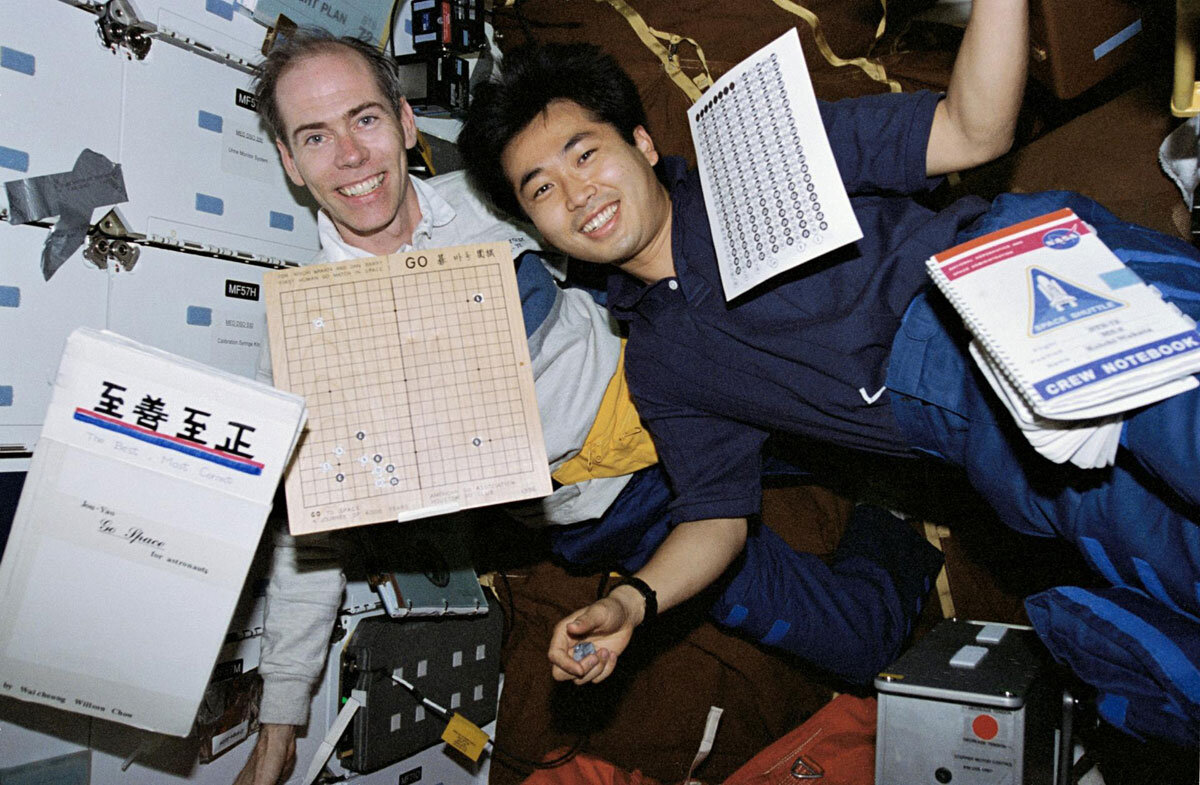

Astronauts Daniel Barry and Koichi Wakata relax and build community with an in-space version of Go. Photo credit: NASA.

4. Connect with community

Social isolation is a significant source of stress in spaceflight and staying connected with family and friends is hugely important to astronauts’ mental health. Thankfully, staying connected is much easier for us here on Earth than it would be for someone on their way to Mars.

I am certainly spending more time than usual connecting with people online and there are many examples of people connecting virtually in a meaningful way for coffee dates, dinner, exercise, and more. My husband’s improv theater group is continuing to meet and play games online, my son has set up a virtual lunch group so he can continue to have lunch with his regular gang, and our friends in Ireland have challenged us to a quiz night and brownie bake-off this week.

With a little ingenuity, we might also find non-virtual ways to connect. Here in Barcelona, the city opens its windows at 8pm every night to applaud health care workers, there are musicians are giving balcony concerts, and there are other “open window” events scheduled in the evenings, like singing ‘Cumpleaños Feliz’ for all the March birthdays or doing group aerobics dressed in classic Jane Fonda attire. While these kinds of collective actions may work better in dense urban areas, one could imagine something similar coordinated on a neighborhood basis, through the block-watch or neighborhood email list.

A space of one’s own is important, even if it’s tiny. Here, astronaut Sandra Magnus poses in her private quarters on the ISS. Photo credit: NASA.

5. Keep the peace at home

For some people, the more immediate problem may be not too little social interaction but too much. Being cooped up with other people can certainly be a problem in space. Valentin Lebedev, a Soviet cosmonaut on Salyut 7, described how toward the end of his 211-day mission, he and his crew-mate and friend, Anatoly Berezovoy, were so alienated that they avoided talking to one another and kept to opposite ends of the capsule.

The number one thing astronauts talk about when asked how they deal with other people in space is the importance of privacy – even if that means a private sleeping space the size of a shower stall. It should be easier, but no less important, to find some private space and time for the people in your household.

In addition to taking some private time, astronauts also work to keep on good terms with their team by building social time into their schedule – having group meals, for example, or playing micro-gravity soccer. While gravity here on Earth means that our activities will look a bit different, enforced family confinement can be a great opportunity to do things together. No one is rushing off to meetings or social engagements, so you can take advantage of the time to chat, play games, or cook together.

Astronauts tweak their environment and activities to stay mentally fit while living and working for long periods of time in a small space that can feel both isolated and crowded. Pictured here are the Expedition 21 crew members on the ISS Harmony module. Photo credit: NASA.

For many of us around the world, this is a time of stress, uncertainty, and confinement to our homes. The good news is that people have been living, working, and thriving in spaces more isolated and smaller than our homes and for periods much longer that we will likely have to endure (the average stay on the ISS is 6 months and the anticipated time for a mission to Mars is 2.5 to 3 years).

Space exploration is an extreme example of confinement, isolation, challenge and uncertainty. But contrary to what David Bowie sings … “For here am I sitting in my tin can; far above the world. Planet Earth is blue; and there’s nothing I can do” … there is actually a great deal that astronauts can do to keep in good mental shape during their mission. Likewise, although our current situation may feel out of our control, there are many things we can do to be in control of our home environment and mental health. We will get through this uncertain time together, and perhaps even come out on the other side more unified and resilient than before.